Is it just me, or is there something iffy with the way respect and politeness have evolved in the Philippines? Respect and politeness are shown through both speech and actions.

First off, let’s examine respectful and polite speech in the Philippines.

| SUPPORT INDEPENDENT SOCIAL COMMENTARY! Subscribe to our Substack community GRP Insider to receive by email our in-depth free weekly newsletter. Opt into a paid subscription and you'll get premium insider briefs and insights from us. Subscribe to our Substack newsletter, GRP Insider! Learn more |

Just to bring everyone up to speed, in Filipino/Tagalog, the so-called “national language”, the words po/opo (most formal/polite) and ho/oho (a notch below in formality) are used at the end of sentences or sentence clauses when respectful or polite speech is required. We also use the plural form of the 2nd person pronoun (you) – ikaw is 2nd person singular, kayo is 2nd person plural – also as part of respectful or polite speech. We also have titles and honorifics for members of the family, and other members of society.

Contrast this with the type of more egalitarian societies in the West. The European languages I’ve encountered so far differentiate between a formal you and an informal you. The formal you is used when dealing with people not part of one’s intimate circle, informal you when with close friends and family. In English, however, there’s just “you”.

Respectful or polite speech is more emphasized and is a more integral part of societies like the Philippines where social status and its determining factors, such as age, profession, and rank, play a bigger part in social stratification. A more recent development, I believe, is the peppering of sentences with “Sir” and “Ma’am”, especially in the corporate world and service industry.

When I was younger, one po/opo and ho/oho, either at the end of the first clause, or at the end of the entire sentence was enough. Nowadays, I hear these words, on the average, after every other word. My Bisaya-speaking friends tell me that such excessive use of po/opo and ho/oho has crept into their colloquial speech; their language, at its core, does not use such politeness markers. Furthermore, they perceive excessive use of it as fake and insincere.

Outgoing president Benigno Simeon “BS” Aquino was a noted example; it formed part of why his speeches were rather cringe-worthy. Incoming Vice-President Leni Robredo, as some commentators on social media pointed out, was also doing the same in a recent speech.

One can’t help but wonder how polite speech here has become what it has. Is it because Filipinos are, more than ever, afraid to come off as offensive? Is it because there is an excessive compensation for something else? Is there a hint of submission, deference, or just plain pandering that is going on when speech is excessively polite? Is it just me, or has respect been reduced to superficiality here?

There is an inordinate, often crossing into unhealthy, focus on respect in the Philippines, which finds its way into social interactions, conversations and discussions. Before people accept what you have to say, they have to accept you as a person first. You have to “mind your manners”, which really is a euphemism for “know your place”. You have to have credentials. You have to be associated with the “right people”. You have to mind your tone, lest you come off as angry. All that is reality, regardless of whether or not what you’re saying is logically sound or argumentatively valid. Never mind if adding polite speech markers removes from the impact of what you have to say.

Because I’ve acclimated to Western notions of egalitarianism, I rarely use po/opo and ho/oho, and rarely do the other things I mentioned above in my speech. In fact, I’ve been called out for “talking to my partners as if we were feeling close. Which I think is bullshit.

I’ve worked with more open-minded Filipino and foreigner bosses, who insisted I drop the “sir” or “ma’am”. It was liberating. I believe respect and politeness is conveyed through the overall impression, which is both speech and deed.

So now, let’s talk about how Filipinos approach respect through actions.

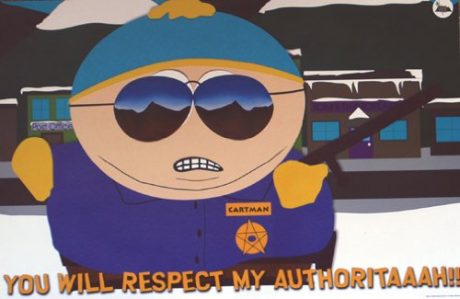

When reminding Filipinos of simple rules and regulations such as, “no littering”, or “fall in line”, one will typically get a response of “DO YOU KNOW WHO I AM?”, or “MIND YOUR OWN GODDAMN BUSINESS!”.

For those who drive and bring motor vehicles, Filipino drivers are notorious for disregarding traffic rules and “trying to get an edge”, especially when they know they can get away with it.

For a people who are “so proud” of their freedom of speech and democracy, Filipino society is all too eager to suppress and beat into submission all who harbor viewpoints and opinions that are any or all of the following: uncomfortable, not popular, or not agreeable.

Three examples. There are many more readily observable ones in Filipino society, but even with just these, a common theme emerges: respect is a one-way street. Respect goes up, but don’t expect it to come back down.

Real and genuine respect in any society is a two-way street. Even in societies like Japan, where politeness and respect have been taken to an art form, this holds true. To further illustrate the Japanese example, we define the senpai, who is the more senior one and looks after the kohai, the junior. The kohai is expected to be respectful and listen to the senpai, and to generally heed his/her teachings/advice and keep from embarrassing him/her. The duty of the senpai is to look after his/her juniors, to give the right advice/lesson, and to prepare them properly for their own comings-of-age. Although it may seem like juniors cannot argue with their seniors, the seniors are expected to be self-accountable, to self-correct if they have committed errors, and not to abuse their authority. Of course there are exceptions to this; there will always be.

When we look at our local example, we find that respect goes all the way up across societal levels, but is generally treated as optional going back down. As children, Filipinos are expected to do all the biddings of their parents without question. In the worst cases, they are treated as property; talking back and asking questions that they don’t want to answer will result in the children being called “ungrateful” or “smart-alecky”. Children are given “subtle” hints to stifle their curiosity, or will be rewarded with smart-alecky pilosopo answers like “galing sa pwet” (came from the ass). And when these children grow up, you can’t blame them for doing it to their own juniors.

What has become of respect in Filipino society?

Superficiality – respect is shown through excessive use of speech markers, but the actions don’t necessarily match the speech.

Lack of mutuality – what goes up never comes down.

Inequality – Filipino society puts unnecessary emphasis on ranks, and its inhabitants are always looking for that “edge” that they can use over others.

Respect is regarded as an entitlement dependent on rank.

True respect, however, is earned and reciprocated. It is based on simple consideration for your fellow man, regardless of status. It is vital for the well-being and development of any society.

Good luck trying to find that here in the Philippines.

[Photo courtesy: ifunny and South Park Shop]

А вы, друзья, как ни садитесь, все в музыканты не годитесь. – But you, my friends, however you sit, not all as musicians fit.

In language the Germans and the French come closest to what you describe.

The Germans will address an unknown, older person always with “Sie” while an known, younger person will be addressed with “du”.

In France, we have the same.

The French will address an unknown, older person always with “vous” while an known, younger person will be addressed with “tu”.

The simplest way of getting true respect is the belief and practice of the moral imperative on not doing unto others what we do not want others done on us. Those that do not practice the moral imperative deserve the ruthlessness of Lex Taliones.

Practicing the moral imperative gives one the moral ascendancy to impose universal values on others.

The use of Po and opo in our culture are cheap and can be outwardly pretentious, unlike in Japanese cultures respect is bowing to each other as a form of agreement and recognizing that respect is earned not something that is publicly spoken.

Perhaps there is a difference in mentality.

One mentality is to be respectful by default – because it is the right thing to do – and then adjust accordingly as the elements in a society interact.

The other is to be blatantly and inherently disrespectful and impolite, and then having to keep up a veneer of politeness just to get what one wants.

I totally agree, politeness in speech does not carry always to action. The Japanese practice of harakiri is their way of gaining back self respect, and a moral responsibility as a consequence of a dishonorable conduct. Politeness in our culture should transcend to action

Ah, “the right thing to do”…

You’d expect that thought to occur to everyone whenever they deliberate on a decision. Unfortunately, as you have probably observed for yourself, this only ever rarely occurs to Pinoys. To them, it’s always: “I’ll do what I want because it’s my business and that makes it right!”

The use of “po” and “ho” is just another form of Fliptard tactics to lube you up before he/she sticks it to you.

Opo and po are Tagalog. I believe they don’t exist in other Philippine languages.

What I still dont understand is the use of words, like ‘ate’, ‘kuya’ and ‘dong’ etc.

Furthermore, I also dont understand the ‘mano’ (I do know what it means, but for me its (too) bizarre).

In my country we even address our boss, team leader, department head by his/her first name.

As I touched on above, it is part and parcel of certain Asian societies, like the Philippines, to attach titles and honorifics when addressing those of similar or higher social status. Social status in these countries is determined by a (usually) complex interplay of age, rank, profession, etc.

Think of the mano as a local equivalent of bowing in Japanese and Korean societies. Again, showing respect for elders is highly valued in certain parts of Asia, Philippines included.

It is different from Western societies, like you’re used to, where societal status matters less.

Neither one is necessarily right or wrong nor superior to the other. They just exist.

I have no respect for politicians, who cheat in elections. I have no respect for politicians, who lie and steal.

Respect is earned; not a right, because, you hold such office. If you respect yourself; your government position. You must not : lie, steal, cheat, etc…

Any evil done by you; that you are trying to hide, will finally come out. My respect on you, will turn into outrage !

The Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino should banish the words po and opo from the Filipino vocabulary as a mere Tagalism a regional form of speech which does not represent the Filipino language.

So what does represent the Filipino language?

Carmichael,

A stupid dialect formed out of conceit, ignorance, and laziness. It’s called “TagLish” (a bastardised combination of Tagalog and English).

Aeta

It is a wise thing to be polite; consequently, it is a stupid thing to be rude. To make enemies by unnecessary and willful incivility, is just as insane a proceeding as to set your house on fire. For politeness is like a counter–an avowedly false coin, with which it is foolish to be stingy.

Fliptards only respect two things: 1) someone or something they cannot understand and thus fear. 2) someone or something they can benefit from.

Everyone and everything else are taken for granted and disregarded.

Unfortunately, you’re right. And even then, respect is tentative for something “they cannot understand and thus fear”. Their first impulse is to judge it and reject it for being “different”

in Polish, they say: “czy pan wesoly?”

which comes across clumsily translated into English as:

“Is sir happy?”

which is addressing someone older in the third person, as a mark of respect, not found in English, but without it being put this way can come across as utterly crass and boorish.

Respect is out when the people have a mere survival level of mentality. That even applies to the middles and upper classes. They believe it’s all about survival.

We are all familiar with the old, and still living, axiom, “children must only be seen.. not heard”. This seems to reveal quite a bit about most ‘class’ or ‘rank’ oriented societies, (not just the Philippines, because this axiom was not ‘made in the Philippines’, and not just in the ‘katagalogan’ either). It doesn’t just betray our values as more biased towards family, clan and tribe; rather than, say, towards the individual; it also seems to put up impediments to self-expression and individualism and, possibly, self-confidence.

‘Culture’ might be justification for the retention of ‘po’, ‘opo’ and other such deferent salutations. This, though, is definitely a poor excuse for failure to breakout in order to achieve one’s own aspirations.. even as these may run counter to clan or tribal mores and tradition. This is, after all, the 21st century, and it surely is a competitive world out there.

Sent from my iPad

Respect left the Failippines 50 years ago and has never returned. What happened to it ? It got sick of the hell-hole and left….never to return again.

Espoo Da JO,

Whatever it was Fliptards called “respect” is nothing more than a pretentious subservience towards others to get what they want. Fliptard don’t know what genuine respect means. If they did the Failippines wouldn’t be what it is today: a fucked up country that had been sold off by its own people for a profit, so it can be exploited by other countries and special interest groups.

Respect to Fliptards is nothing more than a false pride-a heightened sense of self-important—of how they want to see themselves; of how they want to be seen by others; and of how they want to realize their individual goals that are totally out of sync with other Fliptards’ goals, resulting in societal competition and chaos.

Therefore, the “respect [that] left the Failippines 50 years ago and has never returned” is actually a trait that has never manifested itself and allowed to develop among the arrogant and selfish Fliptards, for the simple reason they don’t know what genuine respect means for one’s own country, people, and self.

Aeta

[Edited Version]

Espoo Da JO,

Whatever it was Fliptards called “respect” is nothing more than a pretentious subservience towards others to get what they want. Fliptard don’t know what genuine respect means. If they did the Failippines wouldn’t be what it is today: a fucked up country that had been sold off by its own people for a profit, so it can be exploited by other countries and special interest groups.

Respect to Fliptards is nothing more than a false pride-a heightened sense of self-importance—of how they want to see themselves; of how they want to be seen by others; and of how they want to realize their individual goals that are totally out of sync with other Fliptards’ goals, resulting in societal competition and chaos.

Therefore, the “respect [that] left the Failippines 50 years ago and has never returned” is actually a trait that has never manifested itself and allowed to develop among the arrogant and selfish Fliptards, for the simple reason they don’t know what genuine respect means for one’s own country, people, and self.

Aeta

Begging your indulgence, I should, like to make better sense of an earlier hurriedly written commentary which has confused even myself..

“We are all familiar with the old, and still living, axiom, “children must only be seen.. not heard”. This seems to reveal quite a bit about most ‘class’ or ‘rank’ oriented societies, as it seems to reinforce a pecking order. It doesn’t just betray our values as more rooted in family, clan and tribe; rather than, say, on the individual as a person. It also seems to put up impediments to self-expression and individualism and, possibly, self-confidence.

‘Culture’ seems to be the justification for the retention of ‘po’, ‘opo’ and other such deferent salutations. This, though, is a likely excuse for failure of the young to breakout in order to achieve one’s own aspirations, as these may be seen as running counter to family, clan or tribal mores and tradition… especially if one is really gifted and exceptional. It would be sad if this cultural nicety proves to be a barrier to developing initiative in our youth.”

Sent from my iPad